Kiwi Bird: Exploring Characteristics, Habitat, Behavior, and Conservation Efforts

The kiwi bird, an iconic symbol of New Zealand, captivates the imagination of many with its unique characteristics and behaviors. Recognized for its flightless nature and nocturnal habits, the kiwi is not just a bird but an emblem of New Zealand’s rich biodiversity and cultural heritage. Its plight adds layers of emotional weight to its story, making it a focus of conservation efforts. Within this extensive exploration, we will delve into the fascinating world of kiwi birds, examining their physical features, adaptations, habitats, behaviors, and the threats they face. Weaving through the narrative, we’ll uncover the interesting facts that highlight their significance both ecologically and culturally, providing a comprehensive overview that celebrates this remarkable avian species.

Characteristics of Kiwi Birds

Kiwi birds are one of the most distinctive and recognizable species endemic to New Zealand. With qualities that set them apart from other birds and even fellow avian inhabitants of their ecosystems, kiwis serve not only as biological marvels but also as cultural icons for New Zealanders.

To truly understand the uniqueness of kiwi birds, we can compare their attributes to more common birds. Whereas most birds possess keen eyesight to support their aerial lifestyles, kiwis have evolved to rely primarily on their acute sense of smell. This reliance may be likened to a blind artist creating a masterpiece using only their other senses the kiwi crafts its daily existence in the darkness of the forest floor, where olfaction is key.

- Flightlessness: Unlike sparrows or songbirds that flit gracefully from branch to branch, kiwis are grounded creatures. This flightlessness can be seen as both a limitation and an advantage; it has led to their adaptation to a life on the forest floor, effectively reducing predation risks.

- Body Shape: Their compact, rounded bodies are reminiscent of an egg nature’s perfect design for survival. The stout shape permits them to navigate easily through underbrush, enhancing their ability to seek out food, which primarily consists of insects and worms.

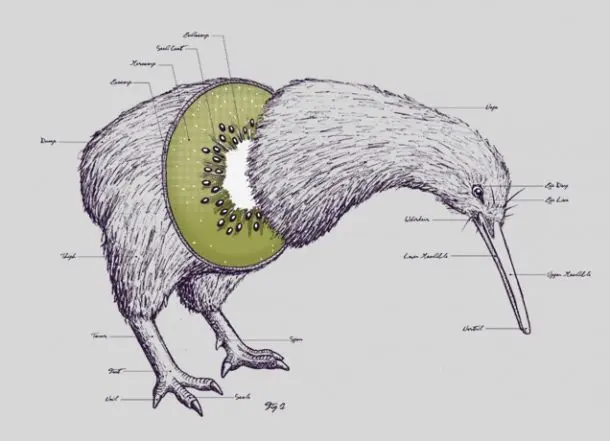

- Unique Beak: The long, slender beak, which can measure up to 5.5 inches, serves as a perfect tool for probing into the ground. If we think of it in terms of a gardener’s trowel, it allows kiwis to dig into the soil and uncover hidden treasures juicy worms waiting beneath the surface.

- Feathers: Unlike traditional feathers, kiwi plumage resembles coarse, hair-like structures a characteristic that serves to camouflaging them effectively against the forest floor. The dull brown hue helps them remain hidden from predators, much like fallen leaves blending into a carpet of foliage.

In summary, kiwi birds possess a remarkable set of characteristics that highlight their adaptations and role within their ecological niche. Their capabilities reflect a fascinating evolutionary path that contributes to the rich tapestry of biodiversity found in New Zealand.

Physical Features of Kiwi Birds

The physical attributes of kiwi birds are remarkable and testify to their unique evolutionary history. Measuring anywhere from 18 to 24 inches in height, these birds are roughly comparable to a domestic chicken, yet they differ dramatically in shape and functionality. Here, we explore their physical features in detail, which encompass extraordinary adaptations to their environment.

Size and Stature: While there is size variation among the five species, kiwis range in weight from about 1 pound for the Little Spotted Kiwi to an impressive 8.8 pounds for the Great Spotted Kiwi. This range underscores the adaptability of kiwis to different forest habitats, accommodating various sizes and weights.

Body Structure: Kiweis’ stout, compact bodies are specially designed for life among dense foliage. As they traverse the undergrowth, their bodies allow them to move stealthily, similar to how a well-camouflaged leaf can blend seamlessly with its surroundings. The absence of flight urges them to navigate their environment more efficiently.

Beak: The most distinctive feature is perhaps the kiwi’s long, narrow beak. Crafted from bone and embedded with sensitive nerves, it allows these birds to detect vibrations and scent in the ground, facilitating the foraging process. Unlike most birds, which rely primarily on sight, kiwis interact with the world through a touching, tactile experience, turning over every leaf to locate hidden meals.

Legs and Feet: Their short, muscular legs, equipped with sharp claws, are crucial for mobility and digging. This design provides stability while navigating uneven forest floors. The leg structure also speaks to their resourcefulness capable of running fast or digging swiftly to find food or evade threats.

Camouflaging Feathers: The unique texture and coloration of kiwi feathers enhance their ability to remain concealed from predators. This adaptation plays an imperative role in ensuring their survival in predator-rich environments. Their plumage, blending earthy tones, mimics the forest floor, allowing them to vanish even from keenest eyes.

Kiwi birds exemplify nature’s ingenuity in design, proving that evolution can lead to fascinating and unexpected adaptations. Their physical features are not just about survival; they are intricately tied to the environments they inhabit and the challenges they face.

Unique Adaptations of Kiwi Birds

The adaptations of kiwi birds go beyond their physical features, extending into behaviors and biological functions that enable them to thrive in their unique habitats. Here, we explore some of the special adaptations that help kiwis effectively navigate the challenges of their environment.

Flightlessness: The kiwi’s inability to fly is one of its most notable adaptations. While this might seem like a disadvantage, for kiwis, it allows them to conserve energy and focus on foraging on the forest floor where food sources are abundant. They navigate the ground with agility, deftly avoiding potential threats.

Acute Sense of Smell: Arguably the most critical adaptation for kiwis is their highly developed olfactory senses. This capability is especially beneficial for nocturnal feeding. With their nostrils located at the tip of their long beak, kiwis can effectively sniff out insects and worms hiding beneath the soil and leaf litter. This adaptation parallels that of a bloodhound with an extraordinary ability to track scents over distances.

Egg Size: Kiwi birds lay eggs that command attention due to their remarkable size they can weigh as much as 20% of the female’s body weight. This significant proportion renders kiwis as the birds with the largest eggs relative to size in the avian world. The investment in large eggs is thought to give chicks a better start by allowing more nutrients for development, enhancing survival odds.

Adaptation to Predation: Many wildlife species evolved with survival tactics; kiwis use stealth and their natural camouflage to thrive. Their behavior during the day being inactive and resting in burrows serves as a protective measure against predation. They rise at night when many potential predators are also inactive.

Behavioral Flexibility: Kiwis’ foraging behaviors reflect their adaptability. They exhibit a methodical approach, using various probing techniques with their beaks to access food sources. Their foraging style can be likened to a treasure hunter gently digging in the sand, always seeking valuable rewards hidden beneath the surface.

Kiwi birds demonstrate fascinating adaptations that enable them to flourish in the rich ecosystems of New Zealand. Their ability to thrive in an environment shared with predation risks speaks to their resilience, showcasing how evolution molds behaviors and anatomical features for survival.

Habitat of Kiwi Birds

Kiwis inhabit a range of environments in New Zealand, showing remarkable adaptability in diverse ecosystems. Understanding their habitat is vital for grasping the significance of conservation efforts aimed at protecting these iconic birds.

- Dense Forests: Kiwis favor lush, temperate rainforests that provide dense undergrowth and abundant leaf litter. These environments not only offer ample food sources but also protection from predators. Their thick canopies help mitigate threats from aerial predators and conceal kiwis from lurking dangers.

- Wetlands and Coastal Areas: Diverse ecosystems such as wetlands and sandy coastal regions also host kiwi populations. These habitats provide essential nutrients and shelter and play a crucial role in their reproductive success. Wetlands allow kiwis to find invertebrates and fruits throughout the year.

- Suburban Areas: Interestingly, as human development has encroached upon natural habitats, kiwis have shown a degree of adaptability to suburban landscapes. They can be found foraging in rough farmland or areas bordering residential zones, where they might exploit the remnants of natural habitats interspersed with introduced weed species.

- Threatened Environments: While kiwis can adapt to various habitats, many face threats due to habitat loss from deforestation, agriculture, and urban development. Conservation initiatives aim to restore and protect these crucial environments to safeguard kiwi populations.

Recognizing the natural habitats of kiwi birds is fundamental to understanding their ecological needs. Conservation efforts play an essential role in protecting these diverse ecosystems, ensuring a sustained future for the kiwi within its native landscapes.

Natural Habitats of Kiwi Birds

The natural habitats of kiwi birds encompass a diverse array of ecosystems, which reflect the evolutionary adaptations that allow these unique creatures to survive.

- Temperate Forests: Kiwis flourish in temperate forests with dense canopies and rich undergrowth. These environments provide not only essential food sources but also cover from predators. The sheltering foliage and complex root systems support the biodiversity that sustains kiwis.

- Shrublands and Coastal Zones: Many kiwis can also be found in scrublands and areas adjacent to the coast. These semi-arid environments enable them to forage for insects and plant material while providing vital nesting spots reminiscent of their forest habitats.

- Wetlands: Wetlands are more than just picturesque landscapes; they are also crucial habitats for kiwis. The abundance of soil invertebrates sustains the diet of kiwi birds, and the intricate waterway systems can act as natural barriers against predators.

- Modified Landscapes: In recent decades, kiwis have adapted to modified habitats often shaped by human activities. In areas where natural vegetation has been replaced, kiwis still manage to survive by foraging in rough farmlands, grasslands, and parks, highlighting their resilience.

Geographic Distribution of Kiwi Birds

The kiwi bird’s geographic distribution is intricately tied to New Zealand’s unique ecosystems. As a flightless bird, the percentages of each species vary, illustrating the effects of habitat loss and predator introduction.

- North Island Brown Kiwi (Apteryx mantelli): This species predominantly inhabits the forests of New Zealand’s North Island, with established populations in Northland and the Coromandel Peninsula. Their ability to adapt has allowed them to hold on despite significant habitat changes.

- Great Spotted Kiwi (Apteryx haastii): Native mostly to the South Island, the Great Spotted Kiwi is particularly associated with the Southern Alps and surrounding national parks. Their population has dwindled due to habitat loss and predation, leading to strict conservation measures.

- Little Spotted Kiwi (Apteryx owenii): This smaller species primarily resides on predator-free offshore islands such as Kapiti Island. Their variability and vulnerability help showcase the effects of feral species on mainland counterparts.

- Okarito Kiwi (Apteryx rowi): Confined to particular regions on the South Island, the Rowi species has benefited from conservation initiatives aimed at habitat restoration and protective measures against predators.

- Tokoeka Kiwi (Apteryx australis): Found in the southern reaches of the South Island, the Tokoeka Kiwi demonstrates adaptability to various habitats, from beaches to wetlands.

Understanding the distribution patterns of kiwi birds underscores the ecological importance of preservation efforts. As their populations dwindle, these conservation initiatives become critical to safeguarding their habitats.

Behavior of Kiwi Birds

Kiwis exhibit unique behaviors that underscore their survival strategies and adaptations in their challenging environments. As nocturnal birds, their behaviors align closely with their dietary needs and predator avoidance.

- Nocturnal Activity: Kiwis are primarily nocturnal, which allows them to forage for food in relative safety from predators. Active at night, their behavior shifts to maximize feeding opportunities while remaining concealed from potential threats.

- Territoriality: These birds demonstrate territorial behaviors, illustrating the necessity of maintaining smaller home ranges. Through vocalizations, kiwis communicate their presence, draw boundaries, and interact with mates. Their calls vary in tone and rhythm, enabling them to assert their territory effectively.

- Social Structure: Despite their territorial nature, kiwis often pair for life, fostering strong bonds characterized by companionship and cooperation. This monogamous structure enhances the likelihood of successful reproduction and chick survival.

- Nesting Behavior: Kiwis do not create elaborate nests; instead, they utilize burrows or excavated areas for nesting. The distinctive approach highlights their adaptability and instinctual survival strategy in evasion of predation.

- Communication: Beyond vocalizations, kiwis also communicate through body language and territorial displays. These interactions reinforce their social structure, contributing to the formation of long-term bonds that ensure both partners participate in incubation and parental care.

Kiwi behavior reflects a remarkable relationship between biology and habitat, showcasing their resilience in coping with environmental challenges. Their nocturnal nature and unique social behaviors form a crucial foundation for their survival within New Zealand’s ecosystems.

Feeding Habits of Kiwi Birds

The feeding habits of kiwi birds are intricately linked to their anatomical features and sensory adaptations. Their foraging behaviors reveal the inherent uniqueness of their ecological role in New Zealand’s forests.

- Diet Composition: Kiwis are primarily insectivores, feasting on a variety of invertebrates, including worms, insects, and spiders. Their flexibility allows them to incorporate fruits, seeds, and fungi when other food sources become scarce.

- Foraging Techniques: Equipped with a long beak, kiwis employ unique probing behaviors to access food stored within the forest floor. They use their sensitive nostrils at the beak’s tip to search for and detect vibrations, enabling them to locate prey effectively.

- Feeding Behavior: Kiwis typically forage alone, moving delicately through the forest floor turning over leaves and sifting through soil. Their careful approach ensures minimal disruption to their environment, much like skilled craftsmen selecting the right tools for their trade.

- Food Preferences: Kiwis generally prefer larger invertebrates, such as earthworms, which offer substantial nourishment. Their omnivorous tendencies allow them to adapt their diet based on availability, showcasing their role as opportunistic feeders within the ecosystem.

- Nutritional Needs: As nocturnal foragers, kiwis fulfill their energy requirements through a nutrient-rich diet comprised of insects and organic matter found in their natural habitat. This feeding habit is essential for maintaining their health and reproductive success.

Feeding habits illustrate how kiwi birds have optimized their survival strategies through specialized adaptations. By depending on their environment’s resources, they contribute to the ecosystem’s health, showcasing the interconnectedness of biodiversity.

Mating and Reproductive Behavior of Kiwi Birds

Kiwi birds possess intriguing mating and reproductive behaviors that reflect their unique life history. While they may appear peculiar through a conventional lens, these behaviors ensure the survival of their species.

- Monogamous Relationships: Kiwis typically form long-term monogamous pairs, a testament to their commitment to family structure and parenting. Once they establish bonds, both parents play active roles in nesting and raising chicks, showcasing their cooperative nature.

- Mating Rituals: During the breeding season, kiwis engage in vocalizations and displays that strengthen their bond. This dynamic communication conveys their readiness to mate while reinforcing territorial claims in their home range.

- Egg Laying: The female lays one, and occasionally two, large eggs that can weigh up to 20% of her body weight. This extraordinary investment not only enhances chick viability but also reflects the physical demands this reproductive strategy imposes on the female.

- Incubation: After laying the eggs, the male takes on the critical role of incubation, which lasts about 70 to 80 days. His warm body provides the essential heat needed for successful development, reinforcing the importance of shared parental responsibilities.

- Chick Rearing: Following hatching, the male remains attentive to the needs of the chicks, accompanying them as they learn to forage and fend for themselves. The nurturing process is vital in ensuring that the young survive predation risks in their formative weeks.

Mating and reproductive behaviors of kiwi birds illustrate the uniqueness of their lifestyles and reinforce their status as remarkable creatures within New Zealand’s ecosystems. The cooperative dynamics between partners emphasize the importance of social bonds in the survival of their lineage.

Conservation Status of Kiwi Birds

Kiwi birds face significant challenges that have contributed to their current conservation status. Classified as “endangered,” the survival of these iconic birds depends on active conservation efforts.

- Population Decline: An estimated 68,000 kiwis remain, with populations declining at a rate of approximately 2% per year. Habitat loss and predation by invasive species lead to alarming mortality rates among both adults and chicks.

- Habitat Loss: Urban development, deforestation, and agricultural practices have severely fragmented the habitat required for kiwis to thrive. The destruction of their natural environments poses an existential threat, making habitat restoration initiatives imperative.

- Predation Risks: The introduction of predatory mammals, such as stoats, ferrets, and cats, poses a grave danger to kiwi populations. Young chicks are particularly susceptible to predation, accentuating the need for protective measures.

- Long-term Conservation Goals: Strategies developed by conservation organizations aim to safeguard kiwi habitats, control predator populations, and support breeding initiatives. With ongoing efforts, the likelihood of increasing kiwi populations becomes more attainable.

Efforts within New Zealand are pivotal for ensuring a stable future for kiwi birds. Understanding their conservation status and recognizing the pressing threats they face underscore the importance of active participation in environmental stewardship.

Threats to Kiwi Bird Populations

The decline in kiwi bird populations is attributed to multiple threats, primarily driven by human activities and environmental changes. To tackle these issues effectively, we examine each threat and its impact on kiwi survival.

- Predation by Invasive Species: Kiwi chicks are particularly vulnerable to predation, with stoats cited as the leading predator. Reports indicate that stoats account for around 50% of all kiwi chick fatalities. This predation rate highlights the urgent need to mitigate invasive pressures on breeding populations.

- Habitat Modifications: Urbanization and agricultural practices continue to encroach on native forests, fragmenting habitats crucial to kiwi survival. Habitat degradation not only reduces available nesting sites but also disrupts the balance of local ecosystems.

- Small Population Vulnerabilities: Many kiwi species face genetic challenges due to their limited population sizes. Inbreeding can result in a loss of genetic diversity, diminishing their resilience to diseases and environmental threats.

- Road Traffic and Human Interference: Increased human activity within kiwi habitats leads to fatal consequences. Vehicle strikes are a significant threat to adult kiwis, and conflicts with domestic animals pose additional risks.

Through identifying the various threats to kiwi populations, conservationists can develop targeted strategies to counter these challenges. Addressing issues at the local, national, and community levels is essential to securing a stable future for these unique birds.

Conservation Efforts for Kiwi Birds

In response to the mounting crises facing kiwi birds, a range of conservation efforts have emerged, representing a significant commitment to reversing population declines and restoring their habitats.

- Intensive Management Programs: Various sanctuaries throughout New Zealand engage in active predator control measures, ensuring that kiwi populations can thrive. For example, the success of the Moehau sanctuary, which has seen a doubling of its kiwi population over ten years, showcases the effectiveness of these strategies.

- Community Initiatives: Collaboration is key to conservation efforts. Community-led organizations assist with kiwi protection across extensive areas, accounting for the active involvement of local iwi (Māori tribes) in nurturing these birds. Their insights often weave traditional ecological knowledge with scientific research.

- Operation Nest Egg: This innovative program involves collecting kiwi eggs from the wild, raising the chicks in controlled environments until they are old enough to survive independently. This approach effectively increases the survival rate of kiwi chicks from a mere 10% to an impressive 65%.

- Research and Monitoring: Continuous scientific research into kiwi ecology ensures that conservation strategies evolve with emerging information. Investigations into predator dynamics, genetics, and habitat requirements inform best management practices.

- Public Awareness: Educating the public on the significance of kiwi conservation amplifies community engagement. Raising awareness about the threats to these birds fosters advocacy and action to protect their habitats and support conservation initiatives.

Through targeted conservation efforts, the future of kiwi birds can be safeguarded. A holistic combination of education, community engagement, and scientific rigor is crucial to ensuring that these iconic birds continue to thrive in New Zealand.

Interesting Facts About Kiwi Birds

The kiwi bird is not just an emblematic figure in New Zealand; it is a creature resplendent with fascinating characteristics and cultural significance. Below are some interesting facts that highlight the uniqueness of this flightless avian wonder.

- Species Diversity: There are five recognized species of kiwi: North Island Brown Kiwi, Great Spotted Kiwi, Little Spotted Kiwi, Okarito Kiwi, and Tokoeka Kiwi. Each species is adapted to specific habitats across New Zealand.

- Largest Egg Relative to Size: Kiwis lay the largest eggs relative to body size in the bird world, with an egg weighing up to 20% of the female’s total weight. This extraordinary reproductive strategy ensures that chicks have ample nutrients at hatching.

- Survival Rates Are Low: Only around 10% of kiwi chicks survive to adulthood due to predation from introduced species like stoats and feral cats. This high mortality rate underscores the urgent need for effective conservation programs.

- Lifespan: Kiwis can live for an impressive 25 to 50 years, showcasing their resilience and strength in the wild. This longevity is often attributed to their low reproductive rates.

- Cultural Significance: Beyond their ecological importance, kiwi birds hold significant cultural value in New Zealand, symbolizing the unique identity of the nation itself. New Zealanders fondly refer to themselves as “Kiwis,” demonstrating the deep connections between the people and their national icon.

- Nocturnal Behavior: Kiwis are primarily nocturnal, utilizing their well-developed sense of smell to forage for food in darkness. This adaptation allows them to evade certain predators.

- Talented Foragers: With their specialized long beaks, kiwis probe deeply into the soil, much like archeologists excavate ancient ruins. This talented foraging technique allows them to locate hidden food sources among forest debris.

- Community Engagement: Numerous community-led initiatives across New Zealand work collaboratively to protect kiwi populations, showcasing a cultural commitment to conserving these remarkable birds.

- Species at Risk: Many kiwi species are classified as endangered or vulnerable, receiving national and international attention for conservation efforts aimed at preserving their habitats.

- Mythical Representation: Kiwi birds feature prominently in Māori mythology, symbolizing selflessness and perseverance. They are considered takata (taonga), sacred treasures, exemplifying the deep spiritual connections that exist between the natives and their environment.

The captivating characteristics and cultural significance of kiwi birds underscore their importance in New Zealand’s ecological and social narratives. As the nation rallies to protect these icons, their preservation becomes a joint responsibility, evoking a sense of unity and stewardship.

Cultural Significance of Kiwi Birds in New Zealand

Kiwi birds are more than just a species; they embody the spirit and identity of New Zealanders. With rich cultural roots, they permeate various facets of New Zealand society, making them an intrinsic element of the nation’s cultural heritage.

- National Emblem: As New Zealand’s national bird, the kiwi symbolizes the country’s unique biodiversity. Its distinctive traits have earned it a prominent place in national symbols, appearing on coins, logos, and even sports teams, thus becoming an integral part of the Kiwi national identity.

- Māori Heritage: For the Māori, kiwi birds hold grave spiritual significance. They are considered taonga, or treasures, and feature prominently in Maori legends and cosmology. The legend of the kiwi speaks to virtues of sacrifice and community, deepening the cultural narrative around the bird.

- Representation of Resilience: The kiwi exemplifies resilience a trait that resonates with New Zealanders. As the nation confronts both environmental challenges and social issues, the kiwi becomes a symbol of hope and adaptability, mirroring the people’s perseverance.

- Cultural Expressions: Kiwi imagery permeates various cultural expressions, including art, literature, and music. Through storytelling and artistic endeavors, the kiwi bird continues to inspire creativity and promote awareness of environmental stewardship.

- Kiwi as Identity: New Zealanders often refer to themselves as “Kiwis,” an endearing term reflective of national pride. This self-identification underscores the deep emotional connection between the people and their iconic bird a bond that transcends biological features to encompass cultural identity.

The cultural significance of kiwi birds is woven into the fabric of New Zealand society. As the derived meanings grow and evolve, the association between the kiwi and the New Zealand people becomes increasingly profound.

Myths and Legends Surrounding Kiwi Birds

Kiwi birds are steeped in rich legends and folklore, particularly within Māori culture, which adds depth and meaning to their existence in New Zealand. These stories not only serve as symbolic representations of cultural values but also foster connections to the land and its inhabitants.

- The Legend of Tānemahuta: The Māori legend of the kiwi centers on Tānemahuta, the god of forests and birds. According to the tale, as Tānemahuta recognized the plight of his tree children suffering from destructive insects, he summoned various birds to assist. The brave kiwi answered the call, sacrificing its ability to fly. In doing so, it gained strong legs capable of navigating the forest floor.

- The Transformation of Birds: Those birds that declined to help faced dire consequences, with Tūī marked for cowardice with striking white feathers. This element of the tale imparts a moral lesson about the importance of community responsibility and the consequences of inaction.

- Symbol of Sacrifice: The kiwi’s transformation from a flying bird to a flightless creature symbolizes selflessness. This representation resonates with the Māori worldview, which places great emphasis on community and individual contributions toward collective welfare.

- Kiwi in Cultural Expression: The mythical narratives surrounding kiwi birds continue to inspire various forms of cultural expression. From art to performance, their stories reflect the unique artistic tendencies of the Māori people while emphasizing their connection to the natural environment.

- National Pride and Identity: Beyond mythology, the kiwi has also become a national symbol for New Zealand, reinforcing the qualities of resilience and adaptability. The connection between Kiwis and their famous bird speaks to a shared identity marked by pride and unity in diversity.

The rich tapestry of myths and legends surrounding kiwi birds speaks to their cultural significance in New Zealand. These stories continue to be shared, reminding both locals and visitors alike of the valuable lessons that nature and history impart.

Conclusion

The kiwi bird stands as a remarkable testament to the unique biodiversity of New Zealand and a profound symbol of the cultural identity of its people. With distinctive physical features and intriguing behaviors, kiwis navigate their environments with adaptations that speak volumes about nature’s ingenuity.

From their enchanting habitats across New Zealand’s forests to their fascinating reproductive strategies, the kiwi encapsulates both the ecological richness and the cultural heritage of the nation. However, the pressing threats they face, including habitat loss and predation from invasive species, highlight the urgent need for continued conservation efforts and community engagement.

As we immerse ourselves in the world of kiwi birds exploring their behaviors, adaptations, and cultural significance we nurture a deeper appreciation for not just the species itself but also the broader ecosystems it represents. The survival of the kiwi bird relies highly on our collective action, emphasizing the importance of stewardship and dedication to preserving both the avian marvel and the vibrant ecosystems of New Zealand for generations to come.